South Chapel

The south chapel at Doddington has been described as a beautiful specimen of later work in the Early English style. It is thought that there was perhaps an interval of half a century between its erection and that of the nave and north and south aisles. the chapel arch is a plainer version of the chancel arch, and contemporary with it, i.e. early thirteenth century, when the south aisle was also widened, and built to span this wider opening.

The south chapel was dedicated to St Mary the Virgin, whose Tabernacle (ornamental box for the consecrated elements of the Eucharist that rested in the middle of an altar) was repainted by the will of Isoth, widow of Richard Bourne (of the Bourne's of Sharsted Court) who left the large sum of 6s. 8d. for that purpose in 1515. There were bequests, too, for the light above her altar. Thomas Howchon left it two bushels of barley in 1465, and Richard Fylkes the same in 1473. Note the Early English piscina at the east end in the south wall.

The south chapel belonged to the manor of Sharsted (anciently Sahersted) in Doddington, held of the King in Edward I's time by the service "of the half and one quarter of a knight's fee" and it was, no doubt, built by the ancient family of Sharsted of Sharsted Court, as was customary for such families, as a burial place.

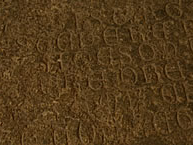

One of their grave stones can still be seen on the chapel floor, the oldest now identifiable in the church, a marble slab with an indent for a floriated cross. This stone had an inscription around the edge in double lines of Lombardic capitals, and by Hasted's time (1782) only the words "..HIC JACET RICARDUS DE SAHERSTADA.." (here lies Richard de Sharsted) could be read.

One or more of the old grave slabs in the chapel pavement, however may have been inverted, and others, now plain, might have belonged to the Sharsteds, who were lords of Sharsted manor until the death of Robert in 1333. He left a daughter as heir, who married John de Bourne of Downe Court in Doddington (of the ancient Kent family of Bourne of Bishops' Bourne) and son of John de Bourne, Sheriff of Kent in the reign of Edward I

A second ancient stone, but of Kentish rag, and also with an inscription in Lombardic characters across its head, now in the chapel floor, was originally in the demolished north aisle of Doddington church, now part of the churchyard, where it was dug up in 1855. The six-line inscription in Norman-French forms a rhyming quatrain commemorating the maiden Agnes, who probably belonged to Sharsted Court or one of the other Doddington manors.

It reads :

ICI : GIST : AGNES : DE : SUTH

CESTE PERE : UOUS : IRREZ : T

OUZ A MESON : ME : COUENT : DE

MORER E : ORE : UOUS : PRIE : ZY

ATER : AMY : CHIER : LE : MAIE : MO

RTE : UOILLET : PENSER :

Translated by Archdeacon E. Trollope and read by him in reporting the discovery of this stone to the Archaeological Institute at London in 1855 :

" Here lies Agnes, under this stone,

All go to the house where I am gone,

Hither hasten, friend most dear;

Think of the poor dead maiden here"

A Mystery

One of the gravestones in the chapel floor has been deliberately defaced to remove the inscription (see photo in Gallery below). Why, when & by whom is unknown.

South Chapel Brasses

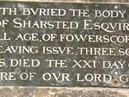

Apart from the indent for the now lost brass of a foliate cross on the slab of Richard de Sharsted, only one brass remains in the south chapel. This is the inscription in English on the stone of Francis Bourne of Sharsted, Esq. who died in 1615 aged 85, and left issue three sons and four daughters.

Medieval Paving

Some medieval paving remains in Doddington church, notably a number of floor tiles in the south chapel.

South Chapel Windows

The most notable architectural feature in the chapel is its fine Early English windows. In the east window, of two lancet lights, some of the glass is original. The thirteenth century circular medallion shows the departure of the Holy Family for their flight into Egypt.

This was used in the 1855 restoration as the starting point for glazing the lancets. Above the east window there is an exquisitely moulded label that is terminated by little corbel heads. They are not placed at the spring of the label arch, but the label there takes a horizontal course for about three inches, before it ends in these pretty corbels.

The South Aisle

the south aisle, contemporary with the demolished north aisle, is Early English. Originally much narrower that it is today, it was widened on the south side to the same width as the south chapel in the early thirteenth century.

South Aisle Windows

Of the two south aisle windows, the older, of two lights, in the south wall is late Early English, contemporary with the widening of the south aisle.

The larger west window, of three lights, is later, belonging to the decorated style (roughly corresponding to the reigns of Edward I through Edward III) divided by mullions, and the head ornamented with bar tracery making geometrical, flowing shapes.

The South Door

The stonework of the south door is contemporary with the widening of the south aisle at the beginning of the thirteenth century.

The south door wood-work, and its lock, as noted by Arthur Hussey in 1852, were medieval, but the present door is modern.

The South Porch

The low buttressed south porch, but with later alterations, may have been built when the south aisle was widened at the beginning of the thirteenth century.